His latest book, while indicating a number of nuances and qualifications concerning both The End of History and the present volume, gives a strong impression that the elements of “decay” in our present democratic institutions are something more than a passing phenomenon, and that liberal democracy may, after all, be facing something more like “decline and fall”.įukuyama’s approach to the development of well-ordered modern states in the 19th and 20th centuries focuses on their need for three key ingredients: an effective administrative bureaucracy, respect for the rule of law and the accountability of state power to a legitimate representative (or even democratic) authority. This meant, in Fukuyama’s words, that liberal democracy might well constitute the “end point of mankind’s ideological evolution” and the “final form of human government” and thus entail “the end of history”. The End of History suggested that the victory of liberal democracy over communism, following its earlier triumphs over hereditary monarchy and fascism, had produced worldwide consensus in favour of this form of government. The underlying message, however, has changed considerably in the intervening two decades.

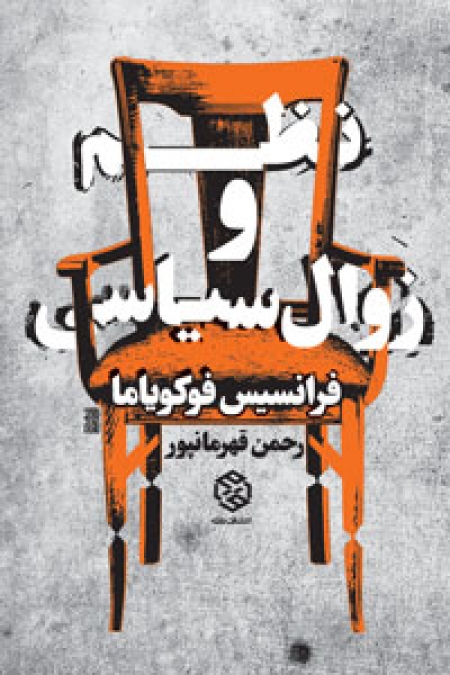

Francis Fukuyama’s latest work forms a direct sequel to his previous one, The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution, and it echoes some of the themes of the controversial tract he published in 1992 following the official end of the Cold War, The End of History and the Last Man.

This principle of government, practically unknown in 1800, is outwardly triumphant in our time, but in practice subject to internal and external challenges, including the insidious danger of decay. This bulky volume surveys the global development of political institutions during the past two centuries, concentrating particularly on the strengths and weaknesses of democracy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)